Simon Chesterman: Intellectual Property Rights and Generative AI

Date:2024-12-23

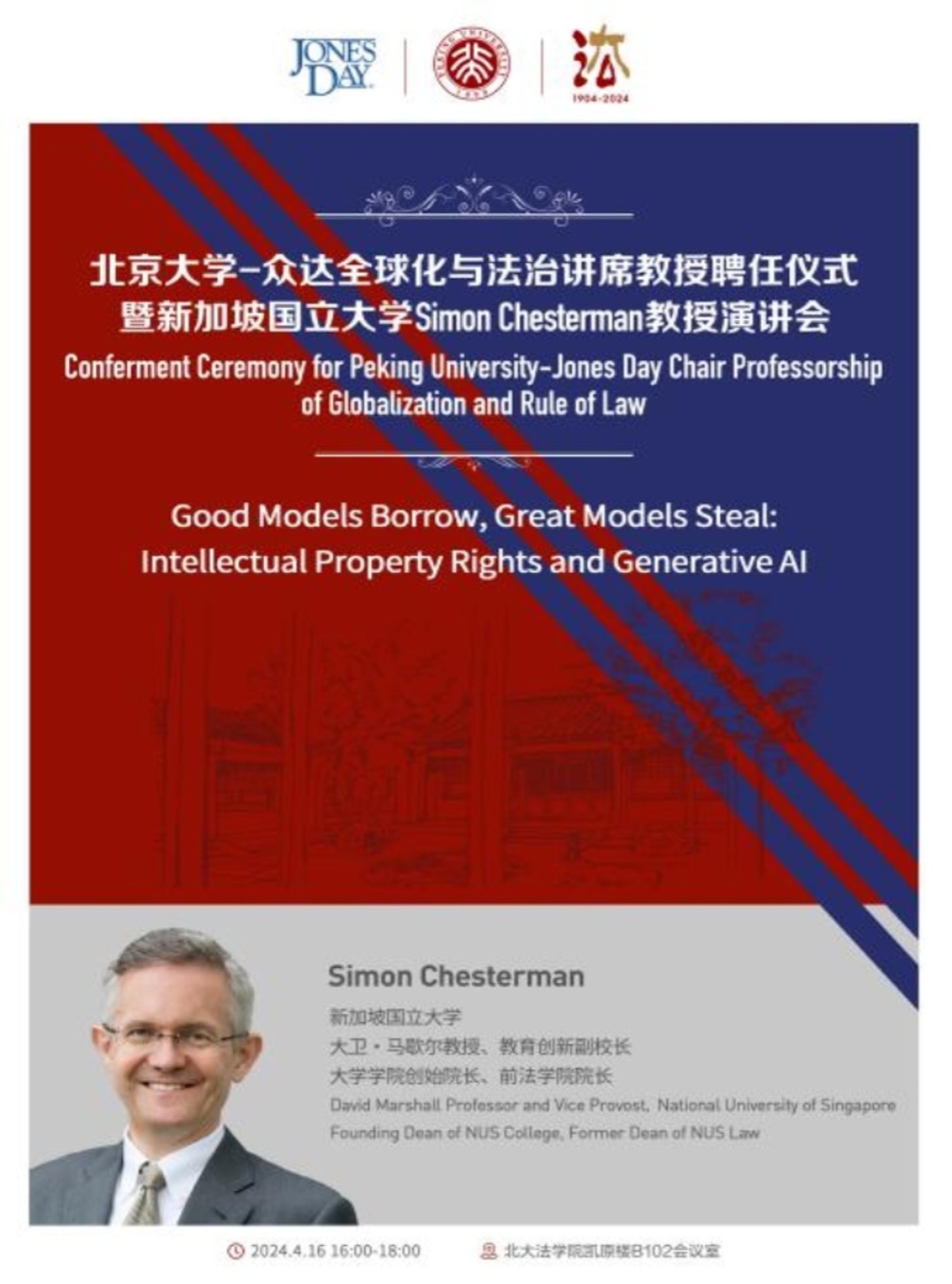

On April 16, 2024, Simon Chesterman, Peking University-Jones Day Chair Professorship of Globalization and Rule of Law, David Marshall Professor and Vice Provost (Education Innovation) at the National University of Singapore (NUS), the founding Dean of NUS College and former Dean of NUS Law, delivered a speech on “Intellectual Property Rights and Generative AI”. The event was attended by Professor Guo Li, Dean of the Peking University Law School, Wang Zhiping (Peter J. Wang), Partner of Jones Day Law Firm's Hong Kong office, and Wu Yichen, Partner of Jones Day Law Firm's Beijing office. The lecture was chaired by Professor Dai Xin, Vice Dean of the Peking University Law School, with Professor Yang Ming, Associate Professor Hu Ling, and Assistant Professor Bian Renjun serving as commentators. Over a hundred teachers and students from within and outside Peking University attended, and the event received a positive response.

This article presents the core points of the lecture in a verbatim transcript.

Simon Chesterman:

1. Introduction

Today, I will mainly talk about "artificial intelligence," which is a challenging topic for scholars because AI is constantly evolving.

Today, AI presents at least three challenges. First, speed. In 2010, a flash crash in the U.S. stock market was caused by high-frequency trading algorithms that outpaced human traders, with AI and related technologies leading to market disruption. Concerns about the speed of AI have led us to introduce mechanisms like stock market circuit breakers. Second, automation. AI can now make decisions autonomously without human intervention, which complicates the assignment of liability, such as the frequently discussed issue of liability for autonomous vehicles. Third, opacity. While machine learning technology has significantly increased AI's capabilities, increasingly complex algorithms have made AI less explainable. Lack of understanding does not mean lack of use. In the medical field, aspirin was used for many years despite limited understanding of its mechanism. However, for legal professionals, the lack of explainability makes it difficult to assign responsibility. The challenge of determining liability for AI-generated harms is exacerbated by “black box” AI systems.

2. The Dual Challenge of AI for Intellectual Property

The impact of AI on intellectual property, or more broadly, can be discussed from both the input and output perspectives.

First, training AI requires large amounts of data input, which may involve unlicensed or otherwise illegal data. OpenAI stopped disclosing its data sources in 2018-2019, possibly due to potential legal risks. As reported recently by The New York Times, OpenAI used YouTube video subtitles to train its AI, which violated YouTube's user agreement. Similarly, Stable Diffusion was sued by Getty Images for infringement. A more complex issue is “fair use”. Companies that develop large language models often defend their use of data as fair use. U.S. courts generally assess the purpose and nature of the use, and if the use significantly impacts the commercial market for the original work, the fair use defense is typically rejected. In 2021, Singapore amended its copyright law to introduce exceptions for computational data analysis, but this has not yet been considered a blanket defense for large language models. In China, the Guangzhou Internet Court ruled in 2024 that training AI with Ultraman data and generating images infringes the copyright owner's rights. The future of these issues remains uncertain.

Second, concerning the output of AI: Can individuals claim intellectual property rights over AI-generated works? If so, who should hold the rights to the output? Historically, the question of whether photography could be protected by copyright was debated. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1884 that photography is not just pressing a button, so it could be copyrighted. This legal process was not shared globally, and Germany only concluded its discussion of this issue in 1965. Similar discussions are now emerging about AI-generated works, such as the copyright of the painting Théâtre D’opéra Spatial; although Jason Michael Allen generated the work by inputting 624 commands into Midjourney, the U.S. Copyright Office ruled that Allen could not claim copyright. In the 1980s, U.K. law allowed limited copyright over computer-generated works, though this copyright is very limited. Unlike other jurisdictions, Chinese courts have recognized in a case last year that under certain circumstances, copyright can be granted for AI-generated works, but this copyright is attributed to the human creator, not the AI. Many people argue that AI-generated works won't surpass human creations in terms of quality, but I believe the more concerning issue is quantity. With AI potentially generating large volumes of low-quality works, this could ultimately undermine human creativity. We've already seen AI-generated articles in top journals, where the authors haven't even properly edited or reviewed the text. This suggests that even scholars are no longer carefully reading their own work.

3. The Regulatory Challenges of AI and Transparency

We do not fully understand how artificial intelligence works, but we know it can outperform humans in many areas. This is not only crucial for intellectual property but also for everyone working in front of a computer screen—AI can do your job better and possibly cheaper. Recognizing this is not difficult, but the challenge lies in how to respond. Especially for small countries like Singapore, we are very cautious about insufficient regulation, as inadequate regulation means exposing people directly to the risks of technology. At the same time, we are also wary of excessive regulation, as it could stifle innovation.

As David Collingridge pointed out in The Social Control of Technology, the ability to control technology and the understanding of its risks tend to be negatively correlated over time. Initially, society has a high ability to control new technologies, but there is little understanding of their risks. As time progresses, our understanding of the risks increases, but our ability to control the technology decreases. This was evident when social media platforms like Facebook were first introduced; we could have taken many actions to mitigate their negative effects on teenagers or to limit the polarization caused by social media. However, we did not take such actions because we were unaware of these risks at the time. Now, faced with emerging technologies like artificial intelligence, we are in a similarly difficult position when it comes to regulation. Countries are concerned that excessive regulation may hinder technological innovation, while insufficient regulation may harm societal interests.

At this stage, I believe what we can do is increase transparency—both during the development and deployment phases of AI. First, in terms of AI development transparency, there is a need to disclose the data used for training the AI models. We do not need to know all the confidential information or trade secrets, but we should at least know what data was used to train the AI models. This would mobilize society to address the challenges posed by AI. Historically, technologies like Napster, which were used to transmit audio files, were often used to share pirated music. Ultimately, Napster came to an end due to a series of lawsuits and legislation because it had become socially unacceptable.

Second, in terms of AI deployment transparency, there needs to be an effort to disclose how AI is being used in content creation. Of course, this is becoming increasingly difficult, as traditional markers like watermarks are no longer effective in controlling AI-generated content. People used to rely on authoritative media outlets (such as The New York Times) for verification, but this method is becoming more difficult as well. Due to the extreme polarization of social opinions, perhaps for half of Americans, even The New York Times and other authoritative media are now considered untrustworthy.

Discussion Segment

Yang Ming:

I will share some of my thoughts on AI from the perspective of intellectual property.

First, we need to reflect on whether we should consider the input and output aspects of AI separately. If we only focus on the input side, many defendants in infringement cases might argue that they haven’t committed any infringement because simple data input might not constitute infringement. If infringement is considered, then the business premise is that AI developers must legally obtain data. This could lead to different business models. For instance, one could directly pay a fixed licensing fee, or allow data providers to receive a share of the revenue later. The former might enhance the bargaining power of data owners, while the latter could increase transaction costs. The issue of AI-generated works is somewhat similar to the case in China involving CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure). Authors provided works to CNKI but couldn't derive any revenue from it. Perhaps we can look to that case to analyze issues related to AI-generated works.

Second, regarding the protection of the output side, we must at least discuss (1) whether AI-generated content constitutes a work under copyright law; and (2) if it is a work, who should hold the copyright. I believe it is difficult, from a technical perspective, to analyze whether the process of generating AI works is purely mechanical, and it is hard to pinpoint the exact boundary between fully random generation and human involvement. From a feasibility standpoint, we may need to return to the issue of standards of proof. We need to establish a reasonable standard that allows both plaintiffs and defendants to demonstrate originality and other copyright requirements in litigation.

Third, we can regulate AI using two approaches: one is using technology to combat technology, and the other is increasing transparency in technology. For example, to address the issue of fake content raised by Professor Chesterman, we could use another algorithm to detect whether the content was AI-generated. Meanwhile, increasing transparency would help us better understand the data behind AI. When it comes to policy choices for AI regulation, we should certainly encourage technological innovation, but this requires a delicate balance of interests among various stakeholders. We may not have just one regulatory path, as our ideas are always constrained by the technology and the era we live in.

Hu Ling:

AI and the internet are conceptually very similar in their original forms. Initially, the internet was understood primarily as a tool to digitize real-world materials, such as pirated books, music, and films. However, in recent years, we have seen the internet develop more mature business models that have changed society. I have previously described the rise of the internet as an “illegal rise” because the internet's business models inevitably competed with traditional production models, violating the legal rules established by those traditional models. Today, generative AI may play a similar role. The key issue is whether the new forms of production or organization represented by generative AI can disrupt old models of production or organization.

We are often concerned about the disruptive potential of generative AI on existing social order. But years down the line, we may not know whether generative AI will be integrated into current social and business models. Looking at China's internet practices over the past few decades, we see that platform companies have influenced rule-making in various ways, gradually evolving existing legal frameworks to accommodate new internet business models. Generative AI might have the same potential, though we don't yet know for sure. I understand that if necessary, the current law can offer a variety of interpretations, but the real question is what kind of interpretation the law should provide, or which party the law should incentivize.

What we can do now is wait. AI stakeholders need to negotiate with data holders and others. We may need to provide an initial price as a starting point for negotiations. Another very important issue is related to competition. What happens if current production organizations refuse to use generative AI? Similar issues arose when the internet was emerging, when old companies tried to suppress the internet industry through monopolistic practices. This might happen in the generative AI field as well.

Bian Renjun:

I’d like to offer four personal insights. First, the difference in the identity of the person creating content with AI may lead to different results, so we should distinguish between outsiders and professionals in the art field. For someone like me, who is not an expert, it is difficult to create beautiful art without AI. But with AI tools, I can do it much better. In this case, the involvement of AI tools seems to align with the purpose of creation under copyright law. However, for artists, this issue may be more complex. For them, creation is often a job, and the intervention of AI tools could be seen as a machine replacing the production process.

Second, we might not need to worry too much about AI replacing human-created content. With advancements in AI technology, it might one day be possible to write 100 books a day. But if this happens, it actually demonstrates that AI needs humans, because AI requires human-created content as its foundation.

Third, copyright law and patent law may focus on different aspects. Copyright law is more concerned with human creativity, so it demands more individual contribution to the creation of a work. Patent law, on the other hand, is more about technological development, where human contribution may not be as important.

Finally, regarding Professor Chesterman’s mention of watermarking, I understand it could be addressed through record-keeping, i.e., encouraging others to document the creative process.

Simon Chesterman:

Thank you all for your comments. When discussing how to regulate AI, I believe we need to distinguish between a tool-based approach and a human-centered approach. The former focuses on the final output, while the latter emphasizes the importance of human concerns. My students in Singapore think AI tools are fascinating, but they also worry that if everyone can easily be trained to become an artist, no one will want to pay for art anymore. This aligns with The New York Times's argument in their lawsuit.

By the nature of technology, we’ve historically worried that technology might impede human thinking. Just like Socrates opposed writing, believing that once thoughts are written down, people would stop thinking. Today, we face the issue that as the cost of creating information decreases, we might be overwhelmed by information, which could limit our capacity to think.

From the perspective of business models in the information industry, profitable modern media companies are either large monopolies or have enough paying users in niche markets. If the information flow in our environment can't generate profit, people won’t want to invest, and we will increasingly rely on AI-generated content. Eventually, we may stop acquiring new knowledge. This is something we need to be cautious about.

Biographical Information for Speaker:

Simon Chesterman is the David Marshall Professor and Vice Provost (Education Innovation) at the National University of Singapore (NUS), as well as the founding Dean of NUS College and former Dean of NUS Law. He is the Senior Director of AI Governance at Singapore’s National AI Office and serves as the Editor of the Asian Journal of International Law. Chesterman has studied in Melbourne, Beijing, Amsterdam, and Oxford. He has taught at institutions including the University of Melbourne, the University of Oxford, the University of Southampton, Columbia University, and Sciences Po in Paris. He was also the Global Professor and Director of the NYU Law School Singapore Program from 2006 to 2011. Previously, he served as a Senior Research Fellow at the International Peace Institute and as the Director of United Nations Relations at the International Crisis Group's New York office. He also worked at the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs in Yugoslavia and interned at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda.

Chesterman has written or edited more than twenty books, including We, the Robots? Regulating Artificial Intelligence and the Limits of the Law (Chinese edition, 《我们,机器人?人工智能监管及其法律局限》, published in 2024). He is a recognized authority in international law and his work has opened a new field of research on the concept of public authority----such as the rules and institutions of global governance, state-building and post-conflict reconstruction, the changing role of intelligence agencies, and the new role of artificial intelligence and big data. He also writes widely on legal education and higher education and has written five novels.