"Compilation of German Environmental Code" at the Peking University Forum on Environmental Law

Date:2024-05-10

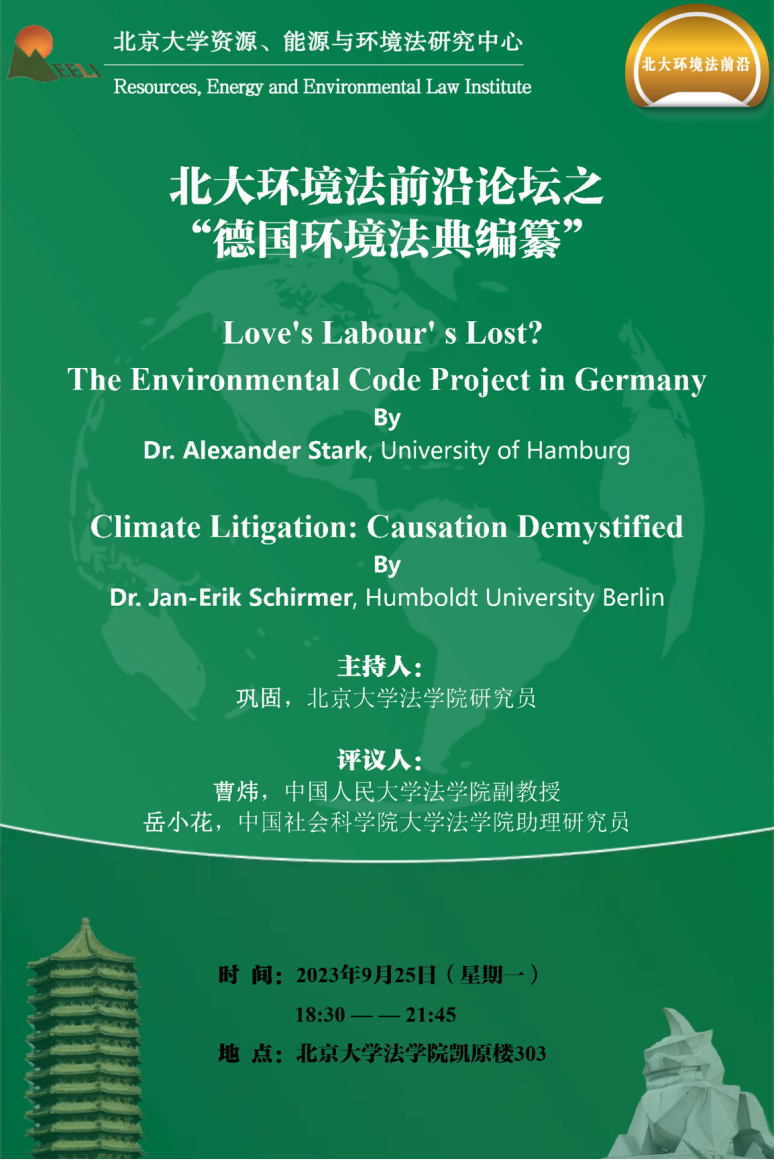

On September 25, 2023, the "Compilation of German Environmental Code" forum, jointly organized by the Research Center for Resources, Energy, and Environmental Law at Peking University and the Hanns Seidel Foundation, took place at Room 303, Kaiyuan Building, Peking University Law School. The forum was hosted by Gong Gu, a researcher at Peking University Law School, and featured presentations by two outstanding young scholars in the field of German environmental law - Professor Alexander Stark from the University of Hamburg and Professor Jan-Erik Schirmer from the University of Humboldt. Cao Wei, Associate Professor at Renmin University of China Law School, and Yue Xiaohua, Assistant Researcher at the University of Chinese Academy of Social Sciences Law School, were invited to provide comments. The event was attended by undergraduate, master's, and doctoral students from Peking University and other universities in Beijing. The forum featured enthusiastic discussions and received a warm response.

Prior to the keynote speeches, Ms. Debora Uta Nadine Tydecks-Zhou, representative of the Hanns Seidel Foundation Beijing Office, delivered the opening remarks. She introduced the foundation's over 20-year history of promoting legal exchanges between China and Germany and highlighted the foundation's increasing focus on climate change and sustainable development in recent years. This focus led to the collaboration between the Hanns Seidel Foundation and the Research Center for Resources, Energy, and Environmental Law at Peking University for the organization of this forum. She expressed her hope for continued communication and collaboration between the Hanns Seidel Foundation and the Research Center for Resources, Energy, and Environmental Law at Peking University to advance cooperation on climate change issues in the future.

The text presents the key points of the lecture in written form.

Professor Stark: "Love's Labour's Lost? The Environmental Code Project in Germany"

First, I need to explain the Chinese translation of the title of this report - "Love's Labour's Lost," which is borrowed from the translated title of a Shakespearean play. The use of this title aims to emphasize the setbacks in Germany's Environmental Code Project, despite the significant time, effort, and resources invested. Although the German environmental code project failed as a legislative project, I want to share the experiences and lessons learned with Chinese scholars. My report will cover three aspects of the compilation of the environmental code: support and opposition, project process, and beneficial experiences.

Firstly, regarding the support and opposition to the compilation of the German Environmental Code. Support can be summarized into three aspects: first, restructuring existing laws. This involves integrating and coordinating concepts, enforcement procedures, and governance tools from existing environmental protection laws, such as the Nature Conservation Act, Soil Conservation Act, and Emission Control Act. Second, amending existing laws. Based on the reality of environmental protection in Germany, existing environmental protection laws are revised and compiled to make them more systematic, comprehensive, and practical. Third, "communicative function." Considering the uniqueness of the German legal system and its acceptance internationally (especially in Asia), the compilation of the environmental code could attract broad international attention and encourage more people to understand.

Of course, with every proposal, there are opposing forces. The reasons for opposition to the compilation of the environmental code in Germany can also be summarized into three points: first, a lack of dynamism. Codification hinders the dynamic development of laws, especially in rapidly changing fields like environmental protection. Overly standardized codes are less adaptable to new environmental issues. Moreover, environmental issues are often interrelated with various professional fields, making it difficult to delineate them, thus making it challenging to determine the scope of compiling an environmental code. Second, inflexibility. Once the code is compiled, it is difficult to modify, making it challenging to adapt to new changes in the field, including changes in non-legal and legal nature. The former includes changes in our living ecological environment, while the latter includes the need for Germany to comply with EU directives. Third, the high cost of transformation. Especially for legal systems that may not be "perfect" in theory but are highly effective in practice, compiling a code may mean pulling them out of their original context, which may hinder their functionality. Another concern expressed by scholars is the fear that code compilation is overly centralized, rather than being completed by many or multiple legislators at different levels, which could fail to fully consider all aspects of environmental protection.

Secondly, the compilation of the German Environmental Code went through more than 30 years and five stages. Initially, in 1976, a professor in Berlin proposed to conduct the compilation project with the Ministry of Environment, but it did not result in a draft. It was not until 1990 and 1994 that two drafts were ultimately formed, outlining the framework and core content of the environmental code. However, at that time, the drafts were compiled by law professors and had issues with being overly academic (progressive academic derivation). In 1997, based on the previous drafts, a Compilation Committee (including judges, experts from various fields, in addition to the law professors who compiled the earlier drafts) produced an official (also translated into Chinese and English) draft. This version somewhat addressed the issue of being overly academic but still had disagreements on some aspects. By 1999, the Ministry of Environment in Germany issued an expert committee draft based on the 1997 draft. However, the Ministry was questioned about its ability as a standalone department to complete the compilation of the code, so this draft did not receive widespread recognition. Finally, in 2008, the second expert committee draft matured and was widely accepted by academia and practitioners. However, in 2009, when it was thought to be ready for formal launch, it ultimately failed due to a lack of firm political will and determination.

Lastly, I would like to introduce the distinctive feature of the “cross-media perspective” in the compilation of the German Environmental Code. Prior to compiling the environmental code, Germany's approach to addressing environmental issues was focused on "point-to-point" governance, neglecting the overall ecological environment. Therefore, during the process of compiling the environmental code, it was proposed to establish comprehensive project approvals or authorizations. Such coordination by one department could consider the overall ecological environment, advance project approvals related to the environment, and simplify approval and management processes of relevant projects. Although the environmental code was not successfully compiled, the concept and system of the "cross-media perspective" have been recognized and developed in other environmental legislation.

Before concluding the report, I would like to quote a comment from the famous German civil law scholar Karsten Schmidt regarding the German Civil Code, which roughly translates to, "The code is no longer a tool for shaping legal order. The transition from bourgeois authoritative states to open-based industrial societies marked the end of the great code era. The fragmentation and cyclicity of laws are now a part of democratic industrial societies."

Professor Schirmer: "Climate Litigation: Causation Demystified"

The focus of my report is on how Germany addresses the issue of determining causation in climate litigation using the Civil Code (Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch), a century-old "old" legal code.

In Germany, climate litigation includes two types: vertical cases where individuals sue the state and horizontal cases where individuals sue companies. A typical example of the former is the well-known German climate activist case "Neubauer vs. Germany," but such cases are rare, with more common cases being horizontal. Horizontal cases can be further divided into forward-looking and backward-looking cases. An example of the former is the Volkswagen case in Germany, where a farmer sued Volkswagen for continuing to produce vehicles with internal combustion engines that affected his agriculture and health, demanding the company to cease production. His lawsuit was dismissed in the trial court, and similar appeals failed subsequently. A typical example of the latter is the "Lliuya vs. RWE" case in Germany, which will be analyzed in this report concerning the determination of causation in German climate litigation. In this case, Lliuya alleges that RWE, as Germany's largest energy company, emitted substantial greenhouse gases through coal-fired power plants over several decades, causing global warming, melting glaciers near his residence, leading to rising lake levels and flooding his property. Lliuya sued RWE seeking compensation for his losses. The court partially granted Lliuya's claims by reimbursing the expenses he incurred for reinforcing and elevating his house. However, the court did not support climate litigation-related aspects of the case. I will further analyze the key dispute focus of causation determination in the case of "Lliuya vs. RWE."

Firstly, the causation chain to be proven in this case can be divided into three parts: 1. Whether greenhouse gas emissions cause climate warming, with RWE's contribution percentage; 2. Whether climate warming causes glacier melting; 3. The contribution of glacier melting to the risk of flooding homes. Providing evidence for each part of this chain is extremely challenging. The local court that heard this case noted the significant number of emitters in the region, making it difficult to differentiate their greenhouse gas emissions. Establishing a linear causation chain between specific emission sources and particular damages in a highly complex climate change process is challenging. Based on this, the court rejected Lliuya's claims. However, the court's viewpoint was overly pessimistic, as the causation chain of this case can indeed be proven.

Regarding the first part of the causation chain, years of research by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) have conclusively proven that most climate change is caused by human emission of greenhouse gases, a well-established fact. Furthermore, RWE's contribution can be clearly outlined, with various researchers utilizing different methods to determine the specific emitter's contributions. For instance, Heede (2014) calculated emissions based on fossil fuel burning by companies and found that 90 large enterprises contributed to 63% of global emissions, with RWE ranking 23rd with a 0.47% emission share. Licker et al. (2019) further assessed that RWE's activities led to a 0.003°C rise in global temperatures, contributing 0.321% to climate warming. Similarly, evidence supporting the second and third parts of the causation chain exists in studies by Rapre/Checa (2016) and Stuart-Smith et al. (2021) linking glacier melting in Lliuya's residential area to climate warming significantly. Huggel et al. (2020) also demonstrated that glacier melting caused lake levels to rise, leading to the flooding of Lliuya's property. Through the efforts of scientists, the correlation between RWE emissions and the flooding disaster faced by residents near glacier lakes was established to over 95%. Nevertheless, some opponents may argue that risks exist everywhere in daily life; does this fact indeed prove causation? For a legal case, the establishment of causation is determined by judges, not scientists. Therefore, the legal standards for proving causation need to be examined within German cases.

The fundamental principle of the Civil Procedural Rules in the German Civil Code is that judges are the determiners of causation. Conclusions drawn from the Civil Judgments of the German Supreme Court state that judges can reach a standard of inner certainty, eliminating doubts but not necessarily eradicating all uncertainties. The doubts that must be addressed or dismissed depend on logic, experience, and natural law or, more precisely, on widely accepted and recognized scientific bases. Therefore, when judges face uncertainties, expert opinions are sought. If experts believe that causation is highly probable, judges will likely consider it established. In the case of "Lliuya vs. RWE," expert analyses have suggested a probability exceeding 95% for the existence of causation. This expert opinion is not singular but a consensus of experts, even the international climate expert community. Following publication, these viewpoints are continually tested and challenged by peers. Supported by robust scientific evidence, the causation chain in this case should indeed be proven.

However, there are two opposing viewpoints. One perspective argues that individual greenhouse gas emitters contribute minimally to global climate change, and even major emitters like the defendant in this case do not significantly increase the potential risks of climate change. Another argument stipulates that besides proving causation, the question of whether an actor is blameworthy for causing harm should also consider the foreseeability of the consequences from their actions. In the case of climate issues, scholars have long suggested that human activities lead to global warming, but the timing of widespread public recognition remains disputable.

In conclusion, I would like to quote the views of the renowned Austrian legal scholar Antoine to close the report. While Antoine was involved in the compilation of the German Civil Code, he also criticized it, noting issues in the allocation of social resources within the code. He analogized the current state to a hurricane on the sea, where professors in their ivory towers always claim to be powerless. The current "hurricane" is climate change. The challenges faced by legal academics today in addressing climate change are possibly akin to those of a century ago (during the compilation of the German Civil Code). We need to comprehend the potential disasters that climate change could bring through knowledge and rationality and take appropriate actions, rather than naively admitting defeat in the face of them.

Associate Professor Cao Wei's Review

The issues discussed by the two professors today are also the two most concerning issues in the current Chinese environmental law community. Firstly, Professor Stark's viewpoints on codification align with the thoughts of Chinese domestic scholars and are crucial. It is important not to automatically assume that codification is superior to individual laws; we should differentiate between the political and legal demands for codification. Even in Germany, a country with the most advanced codification technology, the compilation of an environmental code has yet to be completed. Aside from political determination issues, the fundamental difficulties encountered in compiling the environmental code in Germany and the unique nature of environmental law that were summarized are also factors that should be considered when compiling an environmental code domestically. Professor Stark's viewpoints on determining the scope of adjustments in the compilation of the environmental code, how to systematize existing environmental protection laws, and how to respond to new changes after the enactment of the code are all very enlightening for us.

Similarly, Professor Schirmer's report on the determination of causation in climate litigation in Germany is also very inspiring to me. One crucial point is that there is a distinction between legal responsibility arising from climate change and environmental pollution or ecological damage. Recently, I noticed that some local governments in China have been implementing carbon emission impact assessments in environmental impact assessments. The central issues involved in the institutionalization of carbon emission impact assessments are very similar to the core issues highlighted in Professor Schirmer's research, as they both revolve around the challenging task of determining causation between emissions sources and their surrounding impacts.

Lastly, I want to address why the issues we are focusing on are so similar to those of the two professors. It is because Chinese legal scholars, especially civil law scholars, have brought back the perspective and mindset of doctrinal legal studies from Germany, which has had a widespread impact on the environmental law community. Therefore, our starting point for research is still law-centric, rather than policy or function-centric. As a result, we can share the same research journey, which is the biggest takeaway for me tonight.

Assistant Researcher Yue Xiaohua's Comments

Firstly, Professor Stark's report vividly and appropriately presents the process of compiling the German environmental code. The motivations for initiating the compilation of an environmental code in China are very similar to those in Germany. To summarize in one sentence, successful codes are generally alike, while unsuccessful codes may each have their own reasons. Regardless of whether it is ultimately successful, the process of codification is also a process of self-improvement in environmental protection legislation, where the code represents an outcome or a form of expression. In China, the compilation of an environmental code helps to enhance the government and society's understanding of environmental protection. However, unlike in Germany, political impetus may be the strongest driving force in gradually setting the compilation of China's environmental code on the right track.

Secondly, in response to the issue of causation raised by Professor Schirmer, it should be noted that the determination of causation in environmental litigation is also a significant challenge, not only in climate litigation but also in general environmental litigation. There are many similarities between the two types of litigation, such as forms of liability. Yet, climate litigation has distinct characteristics, such as the long-term nature of the harms caused by climate change. Additionally, climate change issues may involve the interests of a larger population than typical environmental problems, and the scientific uncertainties are greater. It is a major challenge to determine uncertain risks and causation. Therefore, China is also attempting to address climate change litigation as a specialized type of litigation.

Lastly, I would like to share with you a case from China that occurred in 2016, the "Greenpeace vs. State Grid Gansu Branch" case of abandoned wind and solar power. Of course, the main controversy in this case is not about causation but rather the determination of illegality.

Response from Professor Schirmer:

In the fifth chapter of the draft Environmental Code Expert Committee formed in 2008 in Germany, specific provisions were made regarding carbon emission trading. The reason why this provision only appeared in the 2008 draft is due to the coordination with concurrent EU directives during that time period. The relevant EU directive was issued in 2003, which Germany converted into domestic law in 2004. By the time Germany formed the Climate Protection Act in 2019, the contents of the fifth chapter from the draft were included. It is important to note that in the 2008 draft, the fifth chapter solely focused on provisions related to carbon emission trading, with no other content related to climate change until the formation of the Climate Protection Act in 2019.

Professor Gonggu asking questions.

I have two questions I would like to seek advice from the two professors. The first is regarding the compilation of Germany's environmental code, which was largely led by the German Ministry of Environmental Protection. Other departments outside of the Ministry, such as natural resources or forestry management, did not participate in the process. How did Germany consider the scope of adjustment in compiling its environmental code? How did they decide on prioritizing certain objects like natural resources and forests? The second question is, does Germany have specific rules differentiating causation determination in environmental tort cases compared to general tort cases?

Professor Stark's Response

The compilation of Germany's environmental code was indeed spearheaded by the Ministry of Environmental Protection. However, in Germany, agencies like those managing natural resources and forests are not independent departments but are part of the Ministry of Environmental Protection. While the draft may have specified the German Ministry of Environmental Protection, decisions were made through communication and coordination among various departments. Additionally, during the compilation process, a separate environmental agency was established under the Ministry of Environmental Protection to advance specific legislative projects, facilitating communication and coordination among departments and experts. The only department that did not participate in the compilation work at that time was the Ministry of Economic Affairs, possibly overlooking potential economic impacts. Germany now recognizes that economic, energy, and climate issues are interconnected, placing them under a single department for holistic consideration.

Regarding how Germany navigated the adjustment scope in the compilation of the environmental code, particularly in the context of natural resources and forests, as mentioned by Professor Cao Wei regarding moderate codification, Germany aimed to avoid including excessive regulatory content in the environmental code. Therefore, only aspects explicit to environmental law, such as emission control, water, natural ecology, and ionizing radiation, were incorporated into the code. Other matters concerning forests and soil were regulated through specialized laws. It is worth noting that Germany's Forest Law is not focused on ecological forest protection but rather dictates human activities permissible within forests, with forest protection primarily falling under laws related to natural ecology conservation.

Based on German legal provisions, there are no discernible differences in the rules for causation determination between environmental or climate torts and general torts. However, there is ongoing debate within the German legal community regarding whether the burden of proof for causation should be reduced in fields such as environmental, climate, and medical areas. At present, this discussion remains theoretical, without reaching a consensus. At least from the "Lliuya vs. RWE" case shared today and German precedents, there is no indication of a lower standard for plaintiffs to prove causation in such litigations. It is worth mentioning that in addition to the Civil Code, Germany also has environmental liability laws. In the current discourse, scholars have proposed whether, with an environmental code in place, the environmental liability laws should also be integrated, given their lower burden of proof standards in determining liability for environmental damage caused by specific emissions sources. However, there is no judicial backing for this in practice yet.

Student Question 1

Question 1: Professor Schirmer, hello! I have two questions regarding the "Lliuya vs. RWE" case you shared. Firstly, is the burden of proof for causation in climate litigation too high for ordinary individuals lacking professional knowledge? Secondly, even though a company as large as RWE only contributes 0.47% to climate warming, the plaintiff proposed that RWE should only compensate them for 0.47% of the expenses incurred in dealing with rising water levels to increase the chances of a successful lawsuit. However, the court deemed that this 0.47% compensation was insufficient to offset the plaintiff's losses and ruled against the plaintiff. How do you view this issue?

Professor Schirmer's Response

It is precisely because proving the causation of climate change incurs high costs that many ordinary plaintiffs refrain from pursuing litigation. Environmental NGOs, including those behind the "Lliuya vs. RWE" case, provide financial and legal support. Additionally, since RWE's contribution rate is only 0.47%, the compensation amount claimed by the plaintiff was only 60 euros. This 60 euros is more symbolic, and the key lies in the widespread social attention generated by this case. If this case had been successful, more individuals might have taken similar actions, leading to the accumulation of significant amounts despite the minimal compensation in individual lawsuits. The snowball effect sparked by this case may be where its true significance lies.

Student Question 2

Professor Schirmer, hello! As far as I know, in German civil litigation, the standard for judges' inner conviction is one of a high degree of probability, requiring a confidence level of over 70%. In climate litigation, do the judges' level of inner conviction align with the probabilities in the causal relationship chain?

Professor Schirmer's Response

In many climate litigation cases, it is challenging to quantify probabilities and often relies on descriptive language such as "high probability" or "very likely." The German Civil Code does not explicitly outline the conversion relationship between textual expressions and numerical probabilities. Generally, when a text expresses "very likely" or "high probability," German courts may consider probabilities to range from 80% to 90%, which is already a very high probability. In the "Lliuya vs. RWE" case, the probability far exceeded 80% to 90%, reaching over 95%.

In essence, the level of probability cannot always be numerically expressed and is often based on the judge's own judgment. If a judge believes the standard has been met, they will say "yes." As I mentioned earlier, when judges are unable to make a personal judgment, they may rely on expert opinions. In such cases, if experts believe that the causal relationship is highly likely to exist, then for the judge, the causal relationship is likely considered established.

In conclusion, the standard of a high degree of probability encompasses the judge's inner conviction and degree of certainty, and it does not equate to the probabilities in the causal relationship chain. This standard often involves scholarly and expert arguments and judgments and cannot be precisely described with data.

Closing Remarks by Professor Gong

Thank you to the two professors for your insightful presentations. As it is getting late, I will briefly share some thoughts.

In reality, the reasons for opposition to the compilation of environmental codes in various countries are likely to be quite similar. China does not face any particularly significant obstacles or difficulties in compiling environmental codes. Professor Stark's report provides us with another inspiration, as indicated by the question mark in his title "Love in Vain?" – it suggests that as long as one puts in sincere love, it will not be in vain, right? The eventual union of the prince and princess entering the castle is a delightful ending to witness. But even without this outcome, as long as one has truly loved, genuinely put effort into love, that experience itself is beautiful and unforgettable, and crucial for personal growth essential for everyone's true journey to maturity. Regarding Germany's compilation of the environmental code, although it was not ultimately enacted, it gave rise to numerous academic achievements, clarified many theoretical controversies, and many important institutional innovations have already been reflected in individual laws, greatly advancing and enhancing Germany's environmental legal system. Furthermore, considering the situations and characteristics of the compilation of environmental codes in both China and Germany, we have a great opportunity to further advance and do better. The fact that the German environmental code was not ultimately enacted was mainly due to political reasons, and political support is precisely the significant advantage in the compilation of the Chinese environmental code. Objectively speaking, our current weaknesses primarily lie in legislative technique and theoretical reserves. The compilation experiences of countries like Germany can provide an excellent reference for us. Therefore, by leveraging and capitalizing on our country's advantages while fully absorbing experiences from other countries, we can be optimistic about the compilation of our environmental code, which is worth looking forward to.

Additionally, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Professor Schirmer for his report. The topic he discussed is very cutting-edge, but more importantly, his report tells us that for many complex cutting-edge issues, we may still need to patiently seek solutions starting from traditional legal theories and rules with a spirit of reform to promote the development of legal theories and rules. Our ecological and legal system building should achieve a good balance between environmental enthusiasm and legal rationality, steadily advancing within the framework of the rule of law. Objectively speaking, our environmental legislation in recent years has made substantial progress. Many pioneering ideas in developed countries that are still in the stage of academic discourse have been transformed into rules and put into practice by us. However, in the face of this so-called legislative prosperity, our environmental legal scholars may not be able to truly play the role of "legal scholars." Many of the students present here today are environmental law majors, and this point deserves special attention. We should learn from the two professors and their rigorous rational approach to German legal studies, not only relying on environmental enthusiasm but delving more into specific rules and cases, gradually achieving progress in the rule of law through reform.

Finally, although it is with a heavy heart, I must say thank you. People often say that the success of an academic event can be judged by the ending time. I think we can see from the time on our watches whether today's event was successful or not. I would like to thank the Hans Seidel Foundation and Ms. Zhou Dibo for their careful organization and arrangements. A big thank you to the two professors for their professional and precise presentations. Appreciation to Professor Cao Wei and Professor Xiaohua for their reviews, expanding the dimensions and breadth of our discussions. Thanks to Ms. Zhang Ning for her precise and rapid translation, making our communication efficient and smooth. Gratitude to the student organizers for their thoughtful service. Lastly, I am extremely grateful to all the students who have been present and engaged up to this moment, your presence is a tremendous source of inspiration for the presenters and reviewers, making our discussions truly meaningful. The rule of law for the environment, the building of an ecological civilization, is fundamentally a forward-looking cause that requires young people to bravely shoulder responsibilities and strive forward. As long as you continue to pay attention and support, everything is full of hope.