Paul B. Miller: Fiduciary Relationships, Fiduciary Obligations, and the Justification of Fiduciary Law

Date:2023-05-11

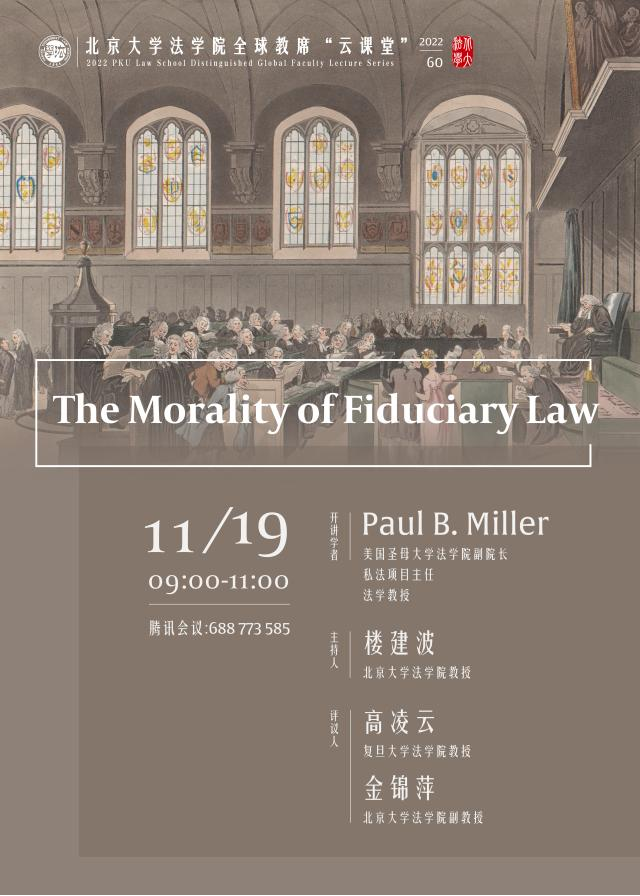

On November 19, 2022, Professor Paul B. Miller, Global Chair Scholar of Peking University Law School, Deputy Dean and Director of the Private Law Program of the University of Notre Dame Law School, gave an online academic lecture on "The Justification of Fiduciary Law". The lecture was hosted by Prof. Lou Jianbo of Peking University Law School, with Prof. Gao Lingyun of Fudan University Law School and A.P. Jin Jinping of Peking University Law School as reviewers. Nearly two hundred teachers and students attended the lecture and the response was overwhelming.

This article presents the core points of the lecture in a transcript format.

|

|

Paul B. Miller:

Fiduciary Law is an emerging field of scholarship and a separate area of law in common law countries.

First, in terms of its relationship to equity, fiduciary law is a product of equity. The earliest trusts were informal, non-legally arranged trusts that reflected an urgent need for property and inheritance in feudal England. Landowners in medieval England would transfer their land holdings to a trusted friend or family member. The relationship was rooted in the social norm of trust, with the expectation that the trustee would manage the property and invest it for the benefit of the beneficiaries. When this trust was betrayed, interested parties petitioned the king and ministers for just relief, hoping that this informal trust would have binding force. Over time, the courts of equity gained experience and clarified in practice the rule for trustees that they should maintain the trust property, invest it properly, and make distributions for the benefit of the beneficiaries, which is now known as the duty of trusteeship. Courts of equity and common law have gradually extended this fiduciary relationship and the obligations of trustees to other contexts, such as the similar status and obligations of company directors. The application of fiduciary norms has thus encompassed different areas of trust law, corporate law, partnership law, guardianship law, family law and agency law, and has been fragmented and inconsistent in each area.

Secondly, in terms of the nature of fiduciary relationships, the dominant view in English and Australian scholarship is that fiduciary relationships are indefinable, however, this view is flawed. Case law holds that fiduciary duties exist on the basis of a fiduciary relationship. A fiduciary relationship is to be defined as one in which one party (i.e. the trustee) exercises discretion over the important practical interests of the other party (i.e. the beneficiary) and the authority of the principal gives the trustee a special power. By virtue of this power, the fiduciary exercises, in place of the principal or beneficiary, the legal capacity derived from his or her legal personality.

Again, with respect to the nature and scope of the fiduciary duty, it is a specific obligation imposed on the trustee and is a response to the characteristics of the fiduciary relationship. A fiduciary duty arises only when there is a fiduciary relationship. All common law countries recognize the duty of fidelity as the core element of the fiduciary duty, which requires the fiduciary to exercise his or her powers in the best interests of the beneficiaries. The duty of care, on the other hand, requires the fiduciary to exercise care and diligence in managing the property and affairs of others as if they were his own. In many jurisdictions, the duty of good faith is also recognized as a fiduciary duty. The duty of good faith requires fiduciaries to engage in certain conduct based on a conscientious promise or belief to take seriously the fact that they are fiduciaries and to recognize the tasks and functions they have undertaken. Some jurisdictions also recognize a duty of truthful disclosure, which requires that fiduciaries should take active steps to disclose to beneficiaries material information relevant to the performance of their functions so that beneficiaries are aware of the decisions made by the fiduciary and the information base on which the decisions are based.

Finally, in terms of the legitimacy of fiduciary law, fiduciary law does not serve a single or a fixed value, but rather a plurality of values. These values are rooted in the fiduciary relationship. In my article "The Justification of Fiduciary Law," I pointed out, first, that a reasonable interpretation of the justification of fiduciary law should be linked to the authorization rule and the fiduciary duty. Because the authorization rule enables the formation and maintenance of the fiduciary relationship, the fiduciary duty determines the possible liability. Second, the legitimacy of the law of fiduciary justice requires consideration of human values and interests. Third, the biplanarity of the fiduciary law in its structure produces its complex character in justification. Fourth, the legitimacy of fiduciary law should take into account the interests of the principal, the trustee and the beneficiary as parties in the formation, performance and termination of fiduciary relationships. Fifth, the legitimacy of fiduciary law should also consider the interests of non-parties, such as the interests of third parties and the public interest.

Gao Lingyun :

Professor Miller tells us about the influence of equity on trust law, the nature of fiduciary relationships and fiduciary duties, and the justification of fiduciary law. As I understand it, Professor Miller argues that general justification lies in the obligations imposed by equity, while special justification rests on the non-fiduciary rule of delegation. One party delegates power to another party for its own benefit or that of its beneficiaries. After this, a legal relationship is formed. If this legal relationship constitutes a fiduciary relationship, equity imposes a duty on the trustee. I agree with Professor Miller that the fiduciary duty is imposed by the law of fiduciaries, but that this delegation relationship is governed by law other than the law of fiduciaries. This theory is reasonable in the context of U.S. law, but may be questionable in the context of Chinese law. This is because there is no uniform fiduciary law in China. Nor is the fiduciary relationship part of the traditional Chinese legal system. Most people would consider fiduciary duties to exist only in the context of fiduciary legal relationships, or at least more closely related to fiduciary law. In China, the law that creates fiduciary relationships and governs fiduciary obligations is, for example, trust law, company law or partnership law, without distinguishing between the law that creates the relationship and the law that imposes the obligation. The drawback of this situation is that no uniform law exists to impose fiduciary obligations on some relationships that are essentially fiduciary. This problem may become more serious in the future. So, we should consider Professor Miller's suggestions and arguments, and can draw on this approach to some extent.

I would like to ask Professor Miller the following questions: First, is fiduciary law part of statutory law or case law in the United States and other common law countries? Second, are the fiduciary duties owed by different fiduciaries the same or different? Third, Professor Miller suggests that the discretionary powers enjoyed by trustees should be emphasized, but how should the line be drawn between discretionary and non-discretionary powers? Most trusts in China are commercial trusts, and usually the trustee only has the right to manage the trust property or the right to distribute the trust income, etc., but not the discretionary power. In this case, how should discretionary power be defined? Fourth, should China enact a separate trust law, or should the status quo be maintained?

Paul B. Miller:

Fiduciary discretion means that the fiduciary has the autonomy to decide how to act, whether to exercise the power, and how to exercise the power in a fiduciary relationship, and this formulation is used by judicial practice. Whether this can be expressed simply as one person's legitimate authority over another person's property and interests, rather than as "discretionary authority," is a question that deserves further consideration. As for the lack of independent fiduciary law in China, we can examine whether there is a system in Chinese civil law that is functionally equivalent to the fiduciary duty and fiduciary relationship, i.e., there are scenarios of authorization and duty of loyalty. Even if there is no unified system of fiduciary law, it can be adjusted in the form of other laws, which is caused by the difference of legal design. It is a complex question about whether the law of faith is statutory or case law in common law countries. It should be said that it is a part of statutory law, case law and equity. For example, agency law should be traced as coming from equity, while corporate law has a statutory basis and the equity experience has been absorbed into case law in the United States. Fiduciary duties in different contexts have similarities or commonalities, only the standard of liability varies from case to case.

Jin Jinping:

I think it is difficult to explain the fiduciary relationship in the civil law system, especially how should the nature of the fiduciary duty be defined? It is neither a statutory obligation nor a contractual obligation, but closer to a fundamental principle. What is the source of the fiduciary duty? This is an inescapable dilemma for scholars in civil law countries. Moreover, the relationship between the provider and the client of social services is now transformed from a fiduciary relationship to a contractual one. If social services are treated as a transaction or contract, then the relationship between the patient and the doctor becomes one of payment and provision of good services according to the contract. If the physician is unable to cure the patient's illness, the patient will consider the physician to constitute a breach of contract. This relationship has exacerbated tensions between doctors and patients and has even led to some extreme incidents. Therefore, I hope to do corresponding academic research and policy advocacy to promote the doctor-patient relationship as a fiduciary relationship. However, such advocacy has difficulties in convincing legislators. Based on the special characteristics of the social service field that are different from other typical contracts in civil and commercial law, I would also like to ask Professor Miller to provide some good research suggestions.

Paul B. Miller:

Regarding the source of the fiduciary duty, while most fiduciary relationships arise from contracts, it can be subject to constraints from both contract and equity. On the issue of the relationship between social service providers and clients, public officials have a duty to serve the public interest and they need to be concerned with the interests of all members of the public, and the interests of different members of the public may be in conflict. So, it may be difficult to apply the fiduciary duty over public officials. An analysis of this issue can draw some inspiration from Locke's work on the history of political philosophy in relation to political trust.

Lou Jianbo:

Professor Miller mentions the different paths of scholarly views and judicial practice, and mentions that when judges rule to impose a fiduciary duty, they will first identify whether a fiduciary relationship exists. Is it possible for judges to argue fiduciary relationship and fiduciary duty sequentially in their reasoning, or just to reason together in a general way? As well, Professor Miller argues that fiduciary law justification is not limited to the parties to a fiduciary relationship, but also extends to other third parties and the public interest. In trusts, it is generally difficult to consider that there is only a relationship between two parties, and other benefit trusts are a tripartite relationship. A third party or the public in a charitable trust may become a party to the fiduciary relationship. Can a discussion of the interests of third parties and the public interest be understood as a discussion of the purpose of the trust?

Paul B. Miller:

On the issue of determining the fiduciary relationship, I have an article entitled "The Recognition of Fiduciary Relationships" and contained in the Oxford Handbook of Fiduciary Law. In the article I mention that the way judges determine a fiduciary relationship is by determining the state of the relationship. This is because legislators and judges in case law and courts of equity have identified generic categories of fiduciary relationships in the past. In the case of a new type of case, the plaintiff should attempt to convince the judge that the relationship between him and the defendant is similar to the fiduciary relationship in those categories. The judges of the Supreme Court of Canada have suggested a series of characteristics regarding fiduciary relationships, trying to think in a systematic way about fiduciary relationships outside of the existing categories.

With respect to third parties and the public interest of society, there is indeed a complexity of possible subject relationships in trusts, which is why I have expanded my analytical framework. I try to identify all possible subjects and include them all in the interest analysis. The interest of the third party mainly refers to the bona fide buyer of the trust property whose reliance interest deserves protection. Based on the consideration of third parties and the public interest of the society, two external restrictions are set for the trustee's behavior, which bind the trustee's behavior in terms of external regulation rather than inherent duty of loyalty.

Speaker Bio:

Professor Paul B. Miller is Associate Dean and Director of the Private Law Program at the University of Notre Dame Law School. He has taught at McGill University School of Law in Canada and has been a visiting scholar at the University of Melbourne and Tel Aviv University in Israel. He holds an M.Phil. from Cambridge University and a J.D. from the University of Toronto. Professor Miller is an international authority on private law, focusing on the law of trusts and corporate law, and his books include Philosophical Foundations of the Law of Trusts, Contracts, Identity and the Law of Trusts, Trust Government, Civil Fault and Justice in Private Law, and The Oxford Handbook of the Law of Trusts. Professor Miller has published in such important journals as the William and Mary Law Review, the University of Toronto Law Journal, the Iowa Law Review, the McGill University Law Journal, and the Osgood Hall Law Journal. He is a member of the editorial board of the American Journal of Law and serves as general editor of Oxford Private Law Theory and its related series, Oxford Studies in Private Law Theory.

Translated by: Wang Shulin

Edited by: Gao Jiaxin