Prof. Burkhard Hess: The Future of Dispute Resolution and the Role of Comparative Law: Using Comparative Procedural Law and Justice Program as a Model for Contemporary Research and Collaboration

Date:2021-12-15

On December 8, 2021, Prof. Burkhard Hess, Global Faculty Scholar of PKULS, founding director of Max Planck Institute Luxembourg for International, European and Regulatory Procedural Law, gave a speech on " The Future of Dispute Resolution and the Role of Comparative Law ". Assistant Professor Cao Zhixun of PKULS served as the host. PKULS Professor Fu Yulin, Associate Professor Liu Zhewei and Assitant Professor Jin Yin from Renmin University of China served as the reviewer.

This article presents the key points of the lecture.

Prof. Burkhard Hess:

How has civil dispute resolution changed now?

1. Globalization and regional integration. Looking at the development of global dispute resolution, there is not only development inside one country’s border, but more and more on a regional basis, such as the European Union in Europe and the "Belt and Road" cooperation in Asia. These regional integrations and developments make dispute resolution and civil procedure law present the necessary trend of unification and coordination.

In the context of the aforementioned globalization and regional integration, our social and economic development requires courts to perform their functions efficiently and fairly. Harmonization in procedural law is now practiced, with both global attempts, such as the Hague Conference on Private International Law, and regional attempts, such as the aforementioned EU. In the context of globalization, there are more and more complex transnational cases that require new types of courts and new means of dispute resolution, such as the International Commercial Court of the Supreme People's Court of China.

2. Technology. The impact of technology is not only as simple as the automation of litigation procedures, virtual courts, etc., but also when artificial intelligence is more involved in dispute resolution, dispute resolution may be truly transformed. AI may not completely replace judges and humans as decision makers, but it can become decision maker’s advisor to a certain extent. The question for us will be how procedural law and the proceedings themselves should respond to this. In any case, this will strongly change the way we live in the future.

3. Crisis in the civil justice system. The crisis in the civil justice system has been much discussed since the late 1990s. At the moment, we should take note of some new developments, such as changes in the number of cases in different countries. In Germany, the number of first-instance cases has decreased by about 40% since the late 1990s. This trend can be seen in Australia and France, but is not yet a global trend. In the United States, only 1% to 3% of all cases actually go to court. What is our explanation for this? Litigation may not be the best way to resolve disputes. Taking Germany as an example, since Germany has not yet adopted electronic litigation, many case materials need to be printed out and sent to the court and different defendants. When the case materials are so numerous that they need to be transported by truck, it will increase the burden on the parties. Therefore, if the electronic litigation system is not adopted, many disputes today will be reluctant to enter the court proceedings, and the parties would rather choose other dispute resolution methods.

4. Alternative Dispute Resolution Approaches. We can learn how to resolve disputes from traditional alternative dispute resolution methods, and we must also take into account the influence of cultural background and local customs. At the same time, more and more disputes are settled through arbitration. There are currently two special types of arbitration commercial arbitration and consumer arbitration. Compared to commercial arbitration, the issues in consumer arbitration are more complex because there is often an imbalance of power between the parties. The question is how to safeguard consumers' rights in arbitration.

5. Personalized options. When disputes arise, there are currently a variety of methods such as litigation, arbitration, mediation, and reconciliation for parties to choose from. This changes how we think about justice, which is not just a state system, it may also be a public service. Different dispute resolution approaches, such as litigation, mediation, and arbitration, are interrelated and affect each other.

6. There is a market-like competition among dispute resolution approaches. For example, the establishment of the International Commercial Court in China shows that China wants to join the international dispute settlement competition. Among them, litigation funding has become a key factor in the competition for digital dispute resolution.

To better understand today's dispute resolution framework, we need to understand the role of the Comparative Procedural Law and Justice (CPLJ) project and comparative law in this context.

1. Why conducting CPLJ project. In today's context of different legal cultures everywhere, comparative law is very important for better consensus and mutual understanding in dispute resolution. We live in a globalized society, but with different legal cultures and different ways of resolving disputes; only by understanding how disputes are resolved in different regions can we learn from other systems. Of course, policymakers can also learn from the practices and dispute resolution methods of other regions. This is not a one-way learning, such as transplantation from the West to the East, this project wants to carry out all-round exchanges. This is also the purpose of the CPLJ Project: to initiate a global comparative law project to better understand how procedural law works in today's world.

2. The formation of CPLJ project. In 2000, a group of outstanding young scholars in the field of procedural law gathered at Renmin University of China for a four-week summer program; it was there that I first met Prof. Margaret Woo. In 2012, the Luxembourg Max Planck Institute for International Civil Procedure, European Civil Procedure and Private Regulatory Procedure Law was established, and I also invited many scholars to participate in the summer comparative procedure law project and discuss together. In 2015, when I visited New York University, Prof. Margaret Woo invited me to co-author a book on comparative civil procedure law, and I readily agreed. In 2016, this writing idea was more fully discussed and expanded in the second IAPL/MPI summer program. Prof. Loïc Caddied, then president of the International Procedural Law Society, became one of the project editors. We jointly decided to write a comparative book. In 2019, this project was partially funded by Luxembourg and was subsequently expanded into a multi-volume compilation. In 2020, the CPLJ project was officially started.

3. Background of CPLJ project. This project is supported by three organizations: the Luxembourg Procedural Law Association, the International Procedural Law Association and the Luxembourg National Research Fund. Among them, the International Association of Procedural Law provides a wealth of experience guidance on the comparative research paradigm.

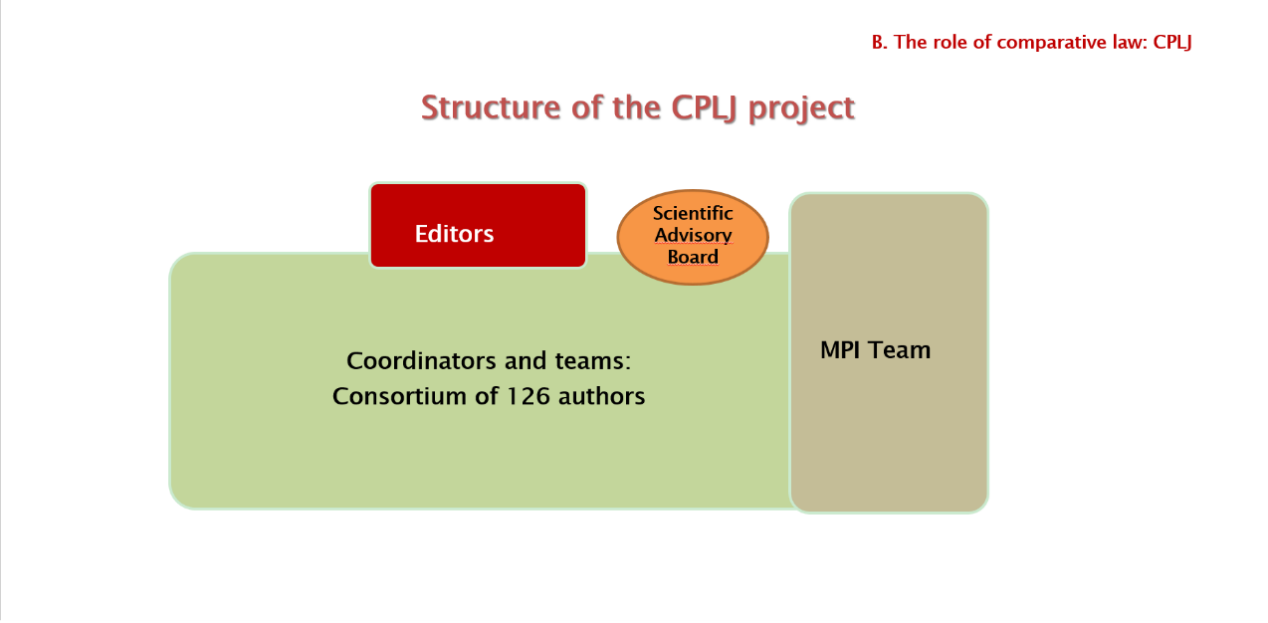

4. the structure of CPLJ project. Currently, the CPLJ Project has four editors-in-chief, Margaret Woo, I, Loïc Cadiet and Enrique Vallines, and an advisory board of 12 scholars, subdivided into 18 research teams from around the world, totaling 126 The participation of famous scholars covers various jurisdictions on five continents, and will be further expanded in the future.

5. Working plan of CPLJ project. The final results of the Comparative Procedural Law and Justice Project are expected in March 2025.

6. The goal of CPLJ project. First, determine the status of procedural law and dispute resolution in the overall comparative law. Second, evaluate and further develop the methods used; third, analyze new issues and future developments, such as digitization, big data, competition between judicial systems, etc.; fourth, try new working methods, especially in virtual forums, to collaborate among various teams with different backgrounds and ages of members; fifth, to create a community of scholars to open up the future for comparative procedural law.

Overall, the CPLJ project is an ambitious project: it covers all areas of civil dispute resolution; it includes many scholars from different cultures and age groups; it aims to compare a large number of legal systems; Ultimately, it goes beyond the narrow legal discipline to take other disciplines into consideration. It is also aggressive in terms of time frame, as the project will be completed within five years as planned. The CPLJ project is considered a true globally collaborative project. Team members should collaborate with each other on the different sections. All working documents are freely accessible and shared on an online platform open to all participants.

About Prof. Burkhard Hess:

Prof. Burkhard Hess is the founding director of Max Planck Institute Luxembourg for International, European and Regulatory Procedural Law (since 2012.9). Prof. Burkhard Hess graduated from the Universities of Würzburg, University of Lausanne and the University of Munich and obtained the University Teaching Certificate in 1996, after which he taught at the Universities of Munich, Tübingen and Heidelberg. Prof. Hess was the Dean of the Law School of the University of Tübingen and the Law School of the University of Heidelberg. He was also a visiting professor at Renmin University of China, the University of Paris and Georgetown University in the United States, a resident scholar at the Center for Transnational Law at New York University, and Adjunct Judge of the Court of Appeal of Karlsruhe. In March 2015, Prof. Hess was awarded an honorary doctorate by Ghent University in Belgium; in May 2016, he was also awarded an honorary doctorate by Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece.

Translated by: Zhang Dayuan