Henk Vording: How does Tax Law respond in Digital Age?

Date:2020-10-23

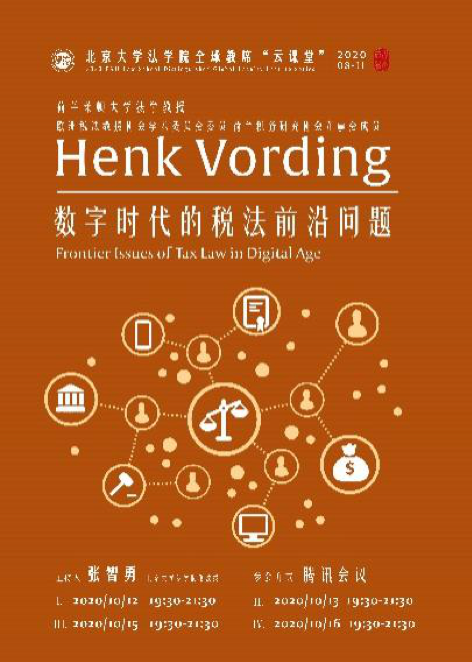

From October 12 to October 16, 2020, Henk Vording, the Global Chair of Peking University Law School and Professor of Leiden University Law School in the Netherlands, held four online academic lectures on the theme of "Frontier Issues of Tax Law in Digital Age". Prof. Zhang Zhiyong presided over the lecture, and more than 200 teachers and students from inside and outside the school participated.

Henk Vording has been a professor at Leiden University Law School since 2006. He was a visiting professor at the University of California, Hastings School of Law. He is also a member of the Academic Committee of the European Association of Tax Law Professors, a member of the Board of Directors of the Dutch Tax Research Association, and a former member of the Dutch Tax Reform Commission. He holds a MA degree in history and a LL.D from Leiden University. In 1986, he was an assistant professor of Leiden University Law School, and in 2004 he was an associate professor of tax law and economics at Leiden University Law School. His courses include Introduction to Tax Law, Tax Philosophy Theory, European Tax Policy. His researches include European and international tax law and policies (with emphasis on corporate income tax), the historical development of tax law and its systems, and the philosophical basis of taxation and redistribution. His recent academic achievements include "How the Netherlands has become a tax haven for multinational corporations" (2019), "The Dutch Tax Policy Statement 2020" (2019), etc.

This report presents the core points of the lecture in the form of transcripts.

1. Difficulties in determining the concept of tax avoidance

Henk Vording: Large multinational companies often avoid taxes through various means, and many developing countries have suffered heavy tax losses as a result. It is generally believed that these large multinational companies should pay a "reasonable share" of taxes, but the "reasonable share" is difficult to define. It is obviously not enough to just look at whether a company’s taxation is compliant, because a large number of companies that are good at using "tax avoidance" methods are proficient in local laws, and there will be no illegal acts in the process of "tax avoidance." In response to this, the G-20/OECD is also constantly discussing countermeasures and has launched the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project (BEPS).

The original intention of regulating “tax avoidance” is not to eliminate all “tax avoidance” behaviors. Many countries have specifically introduced preferential tax policies to attract investment based on the feasibility of cross-border tax planning. In addition, the complexity of tax laws within and between countries, as well as specialized tax planning agencies, all make "tax avoidance" possible. However, there are some excessive tax avoidance behaviors that cannot meet the "reasonable share" standard in any case.

We can re-examine this issue from the perspective of "social contract theory". Social contract theory reminds us that we should consider the possible "free-riding" phenomenon when we make a contract, so as to add various restrictive clauses in the contract. When formulating tax laws, we should also strictly analyze the possible gray areas and consider whether they conform to the basic legal principles. In this way, we can formulate a targeted tax law from the source. Specifically, the tax law can refer to the theory of social contracts and stipulate the conditions that multinational companies must comply with to “enter” a country; in order to solve the dilemma of taxation on a global scale, the scope of the social contract can be expanded to the regional and even international levels to integrate Determine whether the tax share paid by the enterprise is reasonable.

Question: Does "social contract theory" complicate the problem?

Henk Vording: The social contract theory here is mainly aimed at the limitations of the "reasonable share" standard. At present, the tax laws of various countries are not unified, and the treaties between countries are too many to give taxpayers too much room for operation. It is unrealistic to analyze the subjective requirements of taxpayers on a case-by-case basis. Therefore, stricter objective regulations are urgently needed. The social contract theory has pointed out for us that only after clear objective rules are established, can the international community reach consensus and act together.

2. OECD's first pillar plan on taxation for the digital economy

Henk Vording: In 2019, the OECD passed the OECD Pillar 1 proposal and the OECD Pillar 2 proposal on taxation for the digital economy. Among them, the OECD Pillar 1 proposal aims to redistribute taxation rights, and the OECD Pillar 2 proposal aims to delineate the lowest effective tax rate to deal with cross-border taxation issues.

The development of the digital economy has enabled many large technology companies (such as Google, Amazon, Facebook, etc.) to avoid unreasonable taxes through various means. On the one hand, digitalization has brought about tremendous changes in the profit model of large multinational companies. Users bring traffic and advertisements, and trademarks themselves bring extremely considerable royalties. On the other hand, many large multinational companies no longer set up offline entities in many countries or regions. Both add to the difficulty of taxation.

Generally speaking, if a company is to be taxed at its non-domestic place, the company’s local operations must meet the standards of establishing a “permanent establishment”, but this standard is related to the digital economy. The tax issues of the country are often overwhelmed but insufficient.

The 2015 report of the OECD put forward the concept of “significant economic presence”, that is, the digital economy enables companies to deeply participate in the economic life of a country without the need for a tangible existence, which makes the current tax linkage rules and the profit distribution rules are no longer valid. In the 2018 report, the OECD analyzed several major tax challenges of digitalization, including scale without mass, the value of intangible assets of companies, and business models that rely heavily on user participation. In the 2019 public consultation document, the OECD listed three plans for the division of taxation rights in order to allocate more taxation rights to markets or user countries that are closely related to the value created by digital trading activities. These three schemes are user participation taxation model, marketing intangibles taxation model, and significant economic existence taxation model.

In the OECD Pillar 1 proposal formed in 2019, the OECD generally adopted a user participation tax model, that is, first subtract the profits allocated to the company's regular activities under the arm's length principle from the company's total profits, and calculate the unconventional or residual profits , And then determine based on relevant quantitative or qualitative information or simply according to a pre-agreed percentage, attribute part of these remaining profits to the user’s value creation activities, and finally have a user base in the enterprise based on the agreed distribution indicators (such as business income) The relevant profits are distributed among the countries where the users are located.

Question: Are the OECD’s two-pillar proposals fair to developing countries?

Henk Vording: The OECD has always wanted to hear from more countries. However, the OECD pillar proposals are too technical, and many developing countries have neither the ability nor the manpower to truly participate in substantive negotiations. In addition, the user groups of many large technology companies are also concentrated in developed countries. In summary, the consultation process of the Pillar 1 proposal may actually be a contest between developed countries. In contrast, the Pillar 2 proposal will have more participation from developing countries.

3. The OECD Pillar 2 proposal on taxation for the digital economy

Henk Vording: Multinational companies sometimes transfer related profits to low-tax or even tax-free entities, causing the risk of tax base erosion. The Pillar 2 proposal hopes to resolve this risk through joint efforts between countries. When the tax base erosion and profit shift project was born in 2013, the number of countries participating in collaborative tax collection was very limited.

The world's complex tax law system, the existence of tax havens, the requirements of taxation linkages, and the abuse of tax treaties all provide opportunities for tax base erosion. In this regard, the tax base erosion and profit shift project has identified three types of solutions, including the formulation of new regulations, uniform rules, and acceptance of supervision.

The OECD Pillar 2 proposal further introduces the “income inclusion rule” and “undertaxed payment rule” on this basis. The “income inclusion rule” applies to overseas branches of enterprises or controlled foreign companies. According to this rule, if the effective tax rate applicable to the income of a company’s overseas branches or controlled foreign entities in its place of establishment or residence is too low, their related income should be taxed in the country of residence of the enterprise or shareholder. The “undertaxed payment rule” stipulates that certain specific payments made by payers to related parties may not be deducted before tax unless these payments have been taxed at the lowest effective tax rate. In a nutshell, for a cross-border transaction that does not involve a third party, both the residence state and source/market state can levy taxes on it, and the two form a "complementary".

Through the above methods, the OECD Pillar 2 proposal can achieve the lowest effective tax rate, thereby alleviating the tax base erosion and profit shifting problems caused by tax avoidance to a certain extent.

Question: Is territorial tax sovereignty still established under the two-pillar proposals?

Henk Vording: The OECD believes that the country has the right to determine its tax system (for example, whether to tax profits), but its tax sovereignty needs to be established under the basic framework determined by the OECD. For example, the bottom line of the minimum effective tax rate cannot be broken.

4. Taxation issues in the financial industry

Henk Vording: For the financial industry represented by banks, there are usually two methods of government regulation. One is tax and the other is regulation.

There are significant differences between taxation and regulation. Taxation brings fiscal revenue, but regulations cannot do this. Taxation is usually a relatively broad tool, while regulations are aimed at specific behaviors or risks. In terms of results, taxation may affect the society's macro-economy (or at least all users of financial services), and regulations generally only target a certain portion of employees or investors. Both taxes and regulations will increase the cost of banks and their customers. However, taxation policies can ensure that banks receive financial support from the government in the event of a financial crisis, and the implicit implication of regulations is that banks are likely to need to bear their own risks in the future operations. In real life, taxation and regulation usually go hand-in-hand and a two-pronged approach, ranging from the 3% leverage limit to the taxation of specific financial transactions. In general, taxation methods are less sophisticated than regulatory methods.

Translated by: Lu Yiyin

Edited by: Lu Yiyin